OK, so you’re an editor or proofreader who knows Chicago style, but now you need to follow AP. Or you’re a student, and you need MLA for one project and Chicago (or Turabian) for the next—and APA after that.

What are the differences, and where can you learn about them?

Each style has its own book with its own set of rules for everything from punctuation to source citations. The best way to learn about these rules is to sit down with the book (or, if available, the online edition). This brief overview should help you find what you need. (We start with our two favorites, but we like them all.)

Note: In some cases, which style you follow is up to you. In others, your publisher or instructor may have a specific requirement.

Chicago style is based on The Chicago Manual of Style (CMOS for short). CMOS is the guide of choice for many book publishers, and it’s also used by writers and editors in many academic fields, especially in the humanities and social sciences. CMOS covers everything from style and usage to source citations and the mechanics of editing and proofreading. Because of its comprehensive coverage, it’s the go-to guide across many genres and formats, from novels and stories to blogs and creative nonfiction.

Chicago style is synonymous with Turabian, named for Kate L. Turabian, the original author of A Manual for Writers of Research Papers, Theses, and Dissertations. The Turabian manual, which is based on The Chicago Manual of Style, is used by students in history and the arts and other subjects in the humanities and social sciences. In addition to covering Chicago style, including Chicago-style citations, the Turabian manual advises students on research and writing, from topic selection to finished paper.

MLA style is based in part on the MLA Handbook. (MLA stands for Modern Language Association.) The latest edition of the handbook focuses exclusively on how to cite sources. A companion website answers questions about writing-related matters. MLA style is used mainly by students who write papers on literature and related subjects like theater or film.

APA style is based on the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association. The APA manual focuses on writing style and source citations. Because its main audience is students and professionals who write or edit in the social and behavioral sciences, there’s a special emphasis on writing about data and presenting quantitative and qualitative results in tables and figures.

AP style is based on The Associated Press Stylebook. More than half of the AP Stylebook consists of a series of glossaries that cover preferred spellings and abbreviations and how to choose the right term (and avoid the wrong one) for a given context. Because journalists and many other people who work with the news and other current events depend on it, the guide is updated annually.

Beyond that, it’s a matter of style.

For example, Chicago, MLA, and APA all recommend the serial comma; AP does not (except where ambiguity threatens). So “planes, trains and automobiles” is AP style, but you’d need a comma after “trains” to make the grade with Chicago, MLA, and APA.*

In titles, to take another example, Chicago and MLA lowercase prepositions regardless of length. APA and AP capitalize all words of four letters or more, including prepositions. So The Man with the Golden Gun (the classic James Bond novel and film) is correct according to Chicago and MLA; APA and AP would capitalize “with” (but not “the”).† While we’re at it, AP would put the title in quotation marks instead of italics: “The Man With the Golden Gun.”

Possessives are different too. For proper names, Chicago, MLA, and APA always add an apostrophe and an s, even for names that already end in s: Shonda Rhimes’s TV scripts. In AP you’d refer to Shonda Rhimes’ TV scripts.

Most of the differences are like that—a bunch of rules that, taken together, add up to a style.

For source citations, Chicago outlines two systems—(1) notes and bibliography and (2) author-date. APA has its own version of the author-date style, and MLA uses a simplified variation of author-date that is sometimes referred to as author-page. In AP style, sources are usually mentioned or described in the text, with no accompanying bibliography.

There are other differences, but those are some of the highlights.

* The title of the film (in the opening frames, as it moves horizontally across the screen, like a train) is Planes, Trains & Automobiles—which is correct even in Chicago style (because of the ampersand).

† APA style in a reference list would be The man with the golden gun, because titles in APA-style reference lists (but not in the text) are capitalized like sentences. (It’s the little details that make all of this so much fun.)

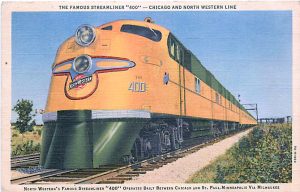

Photo: Chicago and North Western Railway (postcard, 1951)

[Editor’s note (December 3, 2019): This post has been updated to reflect a change made for the 7th edition of the APA manual, published in the fall of 2019. Namely, APA now recommends adding an apostrophe and an s (rather than an apostrophe alone) to form the possessive of names that end in an unpronounced s (e.g., “Descartes’s philosophy”).]

Please see our commenting policy.

Although I’m pretty much a die-hard Chicago fan, I confess I’ve never gotten fully on board with the “Shonda Rhimes’s” apostrophe…

If it’s pronounced, the extra ‘s’ should be there, in my opinion. Keeps it simple. And since I edit books for children, it is much easier for them to understand.