Spotlight on CMOS 7.92

The convention of hyphenating a compound modifier before a noun but not after—as in a well-known author versus an author who is well known—has been Chicago style since the first edition (published in 1906).

Over the years, CMOS has added certain exceptions, including for compounds with all and free, both of which retain their hyphens after the noun, as in a desire that’s all-consuming or a yogurt that’s fat-free.

The 18th edition lists some additional always-hyphenated compounds (besides the ones with all and free) in paragraph 7.92: cost-effective, dyed-in-the-wool, first-rate, high-spirited, ill-advised, old-fashioned, short-lived, and wild-eyed.

Those aren’t the only compound modifiers (also known as phrasal adjectives) that keep their hyphens after a noun. Some can be derived from the compounds listed above—including ill-defined and other terms with ill (see the hyphenation table at CMOS 7.96, section 3, “Compounds Formed with Specific Terms”).

But how will you know whether you’ve found one of these compounds that would remain hyphenated after the noun if it isn’t covered in CMOS? Dictionaries can help, but you may want to consult more than one.

Things That Are Well Known . . .

Well-known things (with a hyphen) are well known (without a hyphen), a principle that goes all the way back to the first edition of CMOS, which featured the examples “well-known author” and “a man well known in the neighborhood” (¶ 167; italics added).

The idea is that hyphens add clarity before a noun but are otherwise unnecessary.

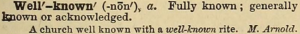

The term well-known was also sufficiently well known to have been recorded in standard dictionaries from that era, as shown by this entry on page 1641 (via the Internet Archive) from an 1898 edition of Webster’s International Dictionary of the English Language (published in Springfield, MA, by G. and C. Merriam):

The literary example in that entry, from the nineteenth-century poet and essayist Matthew Arnold, happens to demonstrate the principle of hyphenation before a noun but not after: “A church well known [no hyphen] with a well-known rite [hyphen].”*

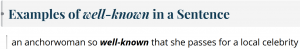

But you won’t find evidence for this convention if you consult the latest dictionary at Merriam-Webster.com, a modern successor (with Merriam-Webster Unabridged) to the International. The entry at Merriam-Webster.com for well-known (as of December 2024) includes an example where the adjective follows the noun it modifies:

The anchorwoman in that example is well-known—with a hyphen. Any writer or editor consulting Merriam-Webster could be forgiven for retaining the hyphen in well-known after a noun. Should you do the same?

. . . May Also Be Well Understood

In those few cases where CMOS and Merriam-Webster disagree, as with well-known after a noun, follow CMOS when applying Chicago style. You would also do this for any compounds that aren’t in the dictionary. For example, the term well-understood isn’t currently in Merriam-Webster, not even the Unabridged (though it is in the OED):

For well-understood, then, you’d retain the hyphen before a noun but not after, per CMOS 7.91 and the hyphenation table at 7.96 (section 2, “adverb not ending in ‑ly + participle or adjective”).

And if you’re going to omit the hyphen in well-understood when it follows the noun, you should do the same for all other compound modifiers with well. That includes the ones in Merriam-Webster, from well-adjusted through well-worn, regardless of how the examples are hyphenated there.

After all, consistency is the No. 2 principle in copyediting. (“Do no harm” is No. 1.)

But what if you find a hyphenated compound adjective that’s listed in the dictionary but doesn’t seem to be covered in CMOS, not even in the hyphenation table?

A Postpositive Phenomenon (and Another Dictionary)

Let’s say you’re in the middle of editing and you come across the adjective clear-cut—after the noun: “That case isn’t clear-cut.” Do you retain the hyphen?

The hyphenation table in CMOS, section 2, under “adjective + participle,” seems to cover this case (where clear is an adjective and cut is a past participle), and the advice there says to leave such compounds open after a noun. But clear-cut itself isn’t listed there, and the process of identifying the parts of speech in a compound isn’t always so (spoiler alert) clear cut. Some of us will consult the dictionary also (or instead).

Merriam-Webster does list the adjective clear-cut, where it has a hyphen. The example included in the definition shows clear-cut before the noun (“a clear-cut decision”). But under “Recent Examples from the Web,” several of the quotations (as of December 2024) feature clear-cut as an adjective after the noun, where it’s hyphenated.

Those “Recent Examples” aren’t from Merriam-Webster, however, and that dictionary doesn’t generally say whether hyphens in compound modifiers can be omitted after a noun; the OED doesn’t either. But at least one major contemporary dictionary does: Collins English Dictionary, which is available at CollinsDictionary.com.

Collins includes separate entries for American English and British English. The entries for British English that are credited to Collins English Dictionary (entries at Collins come from various sources) sometimes include a note relative to hyphenation.

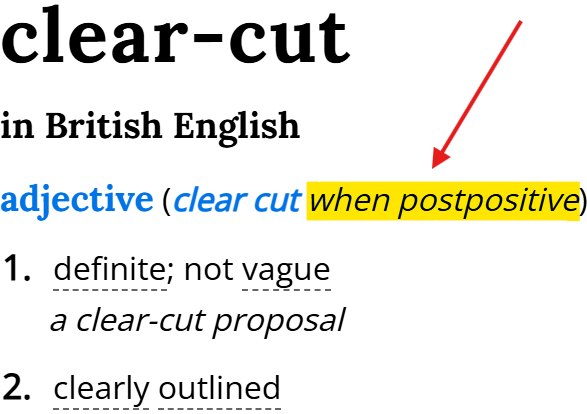

For example, the entry for clear-cut (where the term is hyphenated), includes the following note in parentheses: “clear cut when postpositive.” Here’s that entry:

According to Collins, postpositive means “(of an adjective or other modifier) placed after the word modified, either immediately after, as in two men abreast, or as part of a complement, as in those men are bad.” (See also CMOS 5.83.)

So that entry in Collins explicitly acknowledges the convention of hyphenating clear-cut before a noun but not after, as in a clear-cut case that’s clear cut. Collins does this also in its British English definitions for every well- term it defines (including well-understood).

Collins does not, however, include an unhyphenated postpositive exception for any of the terms in CMOS 7.92—including ill-advised:

Again, those entries carry the label “in British English.” But the basic principles related to hyphenation (including this one) are the same in British as in American English. It wouldn’t be ill-advised, then, to retain hyphenation after a noun for any hyphenated modifier listed in Collins that doesn’t include a postpositive exception (and vice versa).

In other words, whenever you come across a compound that you’re unsure about, Collins—though not necessarily the last word—is yet another resource you can use to check your hunches regarding hyphenation after the noun.

Summing Up

If you don’t know what to do with a compound modifier that’s not listed in paragraph 7.92, check the hyphenation table at CMOS 7.96. If you don’t find an answer there, try Merriam-Webster—or look for the term under the British English entries in Collins to see if there’s an exception there relative to hyphenation.

If you’re still unsure, resist the trend toward postpositive hyphenation and leave the compound open after a noun, provided the meaning of the text remains clear. After all, the main reason to hyphenate a compound modifier is to provide clarity before a noun, not after, a principle that is well established.†

* The example is from Arnold’s essay “A Last Word on the Burials Bill,” in Last Essays on Church and Religion (London, 1877), 208, Google Books. The text there capitalizes “church” and includes a comma: “a Church well known, with a well-known rite.”

† For compounds that remain open before a noun (including compounds formed with ‑ly adverbs), start with CMOS 7.91.

For more on Hyphens see Hyphens and Dashes: A Refresher.

Top image: “Chart with Upwards Trend” followed by a hyphen and “Chart with Downwards Trend,” as rendered in Microsoft Word in Segoe UI Emoji font.

Please see our commenting policy.